Online Interactive Course:

Instructions: Complete all the modules then take the post-training survey to claim CME/CEU. Each module has 3-4 review questions. Answer each question correctly to advance in the module.

This course is presented for review purpose only.

> change log 200904-mt: quiz functionality 200912-jl: tobacco module 200913-mt: tobacco medication modals: table to pills 200914-mt: min-height to modals so doesn't look too short 200914-mt: fixed font import 200914-jl: corrected title and text in nicotine module; 200914-jl: updated SUD tools info 200914-mt: modal-xl 200915-mt: responsive page container size 200915-mt: full hr divider class 200915-mt: table shadows 200916-mt: table header color 200916-mt: b->strong; i->em standard 200920-jl: various formatting-bullet spacing 201005-jl: enter content BI module 201016-jl: added BI video; BI module complete 201023-jl: OUD module (partial);formatting 201025-mt: html validation, badge rework/standardize 201104-jl: add images to OUD module 201104-jl: OUD module content entered; need images and fine-tune formatting 201116-mtjl: OUD module validated and complete 201129-jl: AUD module partially entered 201213-jl: formatting 210103-jl: 210128-mt: tracking 210130-jl: final content edits 211028-jl: started adding M6 211030-jl: finished adding M6 211031-mt: m6 page records entered in db

Evidence-based Screening for Substance Use in Primary Care

Learning Objectives

Completion time: About 10 minutes

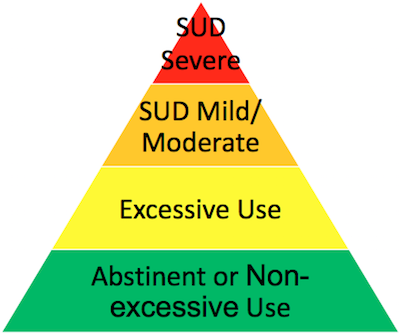

Substance Use Continuum

Substance use exists on a continuum of behavior. Universal screening of patients 12 and older allows us to know where our patients are at on that continuum, so that, depending on where they fall on that spectrum, we can reinforce abstinence or non-excessive use, intervene early before a SUD develops from excessive use, and provide patients with SUDs treatment or referral to treatment.

Most patients will screen as abstinent to all substances or non-excessive drinking. There is no non-excessive limit to nicotine or other substance use besides alcohol. The majority of patients screening positive in most primary care settings, roughly 25% of adult patients, will be at the excessive use level, i.e., they will not have a diagnosable SUD. Only a fraction of patients who screen positive will have a diagnosable SUD, roughly 5-10% of adult primary care patients, for which treatment is recommended.

The hallmarks of substance use disorders (SUD) are:

| Level | Use | Consequences | Repetition | Loss of control, preoccupation, compulsivity, dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUD Severe | ✱ | ✱ | ✱ | ✱ |

| SUD Mild/Moderate | ✱ | ✱ | ✱ | n/a |

| Excessive Use | ✱ | ✱ | n/a | n/a |

| Abstinent/Non-Excessive Use | ✱ or n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

CLICK HERE for the DSM-5 criteria for a formal SUD diagnosis.

Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) DSM-5

Review Question

Your patient is the 19yo daughter of a colleague who is seeing you ostensibly for a birth control visit, but your colleague shared their concerns about her marijuana use, which they think is continuing when she visits her boyfriend on weekends, and contributed to her slipping GPA and losing a merit-based scholarship at college this past semester.

Where do you think this patient will screen on the substance use continuum?

Excessive drinking levels for healthy adults are defined as:

| Persons | Per Occasion | Per Week |

|---|---|---|

| Men (21+) | > 4 drinks | > 14 drinks |

| Women (21+) | > 3 drinks | > 7 drinks |

| Men (65+) | > 1 drinks | > 7 drinks |

| Pregnant | > 0 drinks | > 0 drinks |

| All < 21 | > 0 drinks | > 0 drinks |

The excessive drinking levels are based on counting Standard Drinks, defined as:

| 12 oz. of beer or cooler | 8-9 oz. of malt liquor | 5 oz. of table wine | 3-4 oz. of fortified wine (such as sherry or port) | 2-3 oz. of cordial, liqueur or aperitif | 1.5 oz. of brandy (a single jigger) | 1.5 oz. of spirits (a single jigger of 80-proof) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12 oz. | 8.5 oz. | 5 oz. | 3.5 oz. | 2.5 oz. | 1.5 oz. | 1.5 oz. |

Each standard drink listed across this chart contains the same amount of alcohol by weight.

That is, a 12 oz can of beer contains the same amount of alcohol as a 5 oz, (standard pour), glass of wine, which contains the same amount of alcohol as a single shot of 80 proof liquor or mixed drink made with a single shot.

As another comparison, a 6 pack of 12 oz beers has just a bit more alcohol than a bottle of wine which contains 5 standard-size servings.

A fifth of liquor is a fifth of a gallon (750 ml) and contains just over 25 ounces or 16 standard shots.

Review Question

Your patient is a 54 yo male with a sports related injury, new to your practice. He is drinking 1 glass of wine with dinner nightly on weekdays, and two 40 oz beers after his soccer league games, on both Friday and Saturday evenings, with his teammates.

His drinking:

These are commonly used, evidence-based SUD Screening Tools…

| Screener Name | Substances# | Number of items | Time to administer (minutes) | Administers@ | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASSIST | N,A,D | Multiple*(2-8) | 10 | P and S (S scores) | Built-in feedback, patient ed |

| AUDIT/ AUDIT-C | A only A only | 10 3 | 5 3 | P or S P or S | AUDIT-C for initial screen, full AUDIT if positive |

| CAGE/ CAGE-AID | A only A and D | 4 4 | 2 2 | P or S P or S | Doesn’t distinguish between lifetime/current problem |

| CRAFFT/ CRAFFT-N | A and D N, A, D | 4-9 items 5-10 items | 2-5 2-5 | P preferred P preferred | Only validated screen for adolescents |

| DAST-10 | D only | 10 | 5 | P or S | Often used with AUDIT |

| SQAS SQDS | A only D only | 1 1 | 1 1 | P or S P or S | Rapid screens, distinguish excessive use and SUD |

| TAPS tool | N, A, D | Multiple* (4+) | 5-10 | P or S (auto scores) | Derived from ASSIST, briefer, online tool |

Click on a screener name for more information

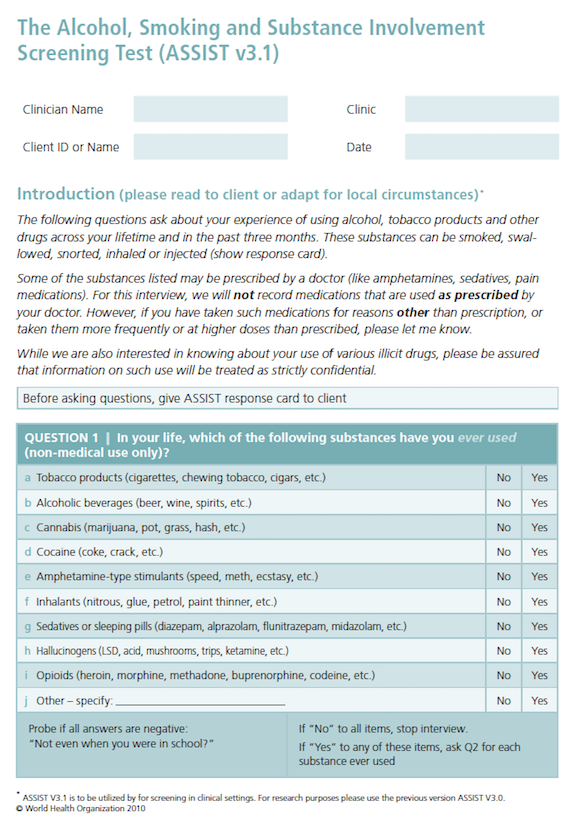

ASSIST Instrument

Score Interpretation

| Alcohol | All other substances | |

|---|---|---|

| Lower risk | 0-10 | 0-3 |

| Moderate risk | 11-26 | 4-26 |

| High risk | 27+ | 27+ |

Additional Notes

Median sensitivity and specificity: 80% and 71%

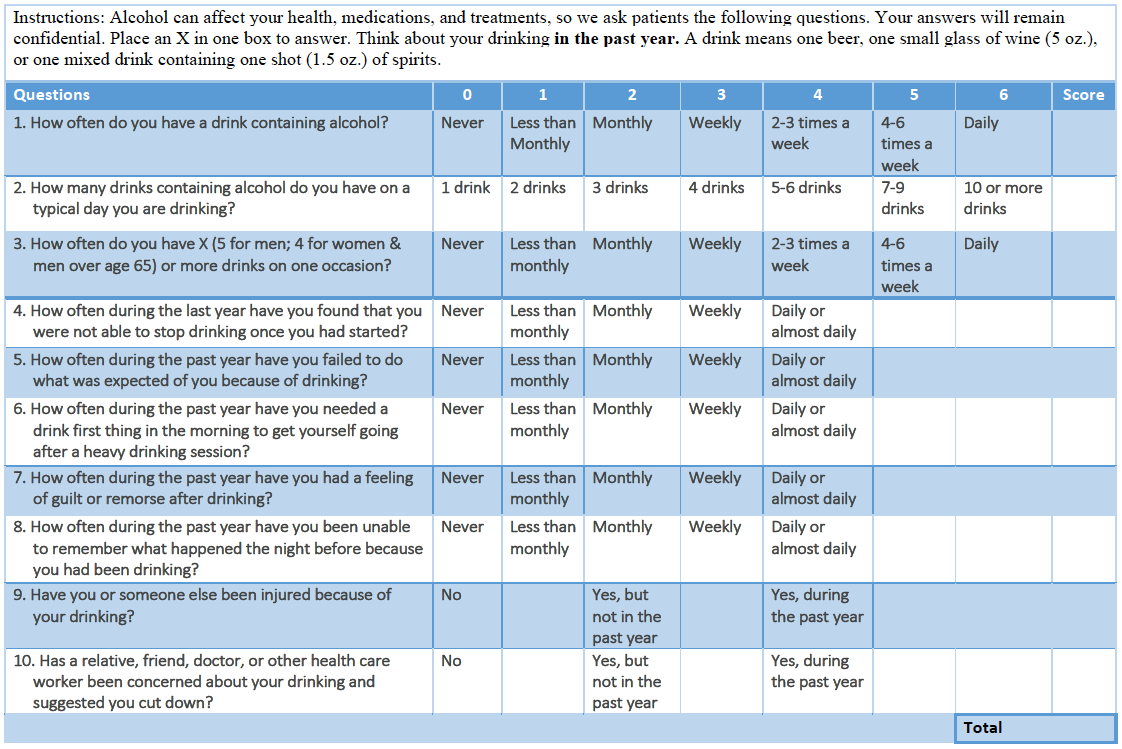

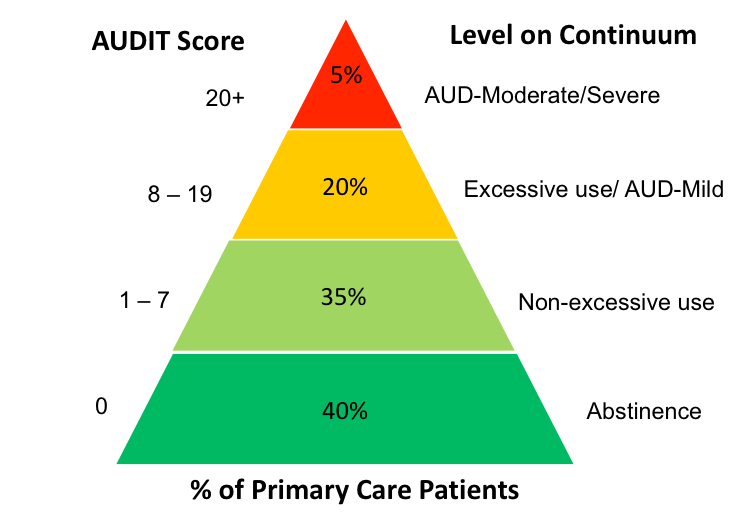

AUDIT Instrument

Scoring

Additional Notes

Median sensitivity and specificity: 86% and 89%

Score Interpretation

Additional Notes

CAGE - Sensitivity and specificity: 77% and 85%

CAGE-AID - Sensitivity and specificity: 79% and 77%

CAGE Source: Ewing 1984. CAGE-AID Source. Brown, R.L. and Rounds, LA Wisconsin Medical Journal 94: 135-140, 1995.

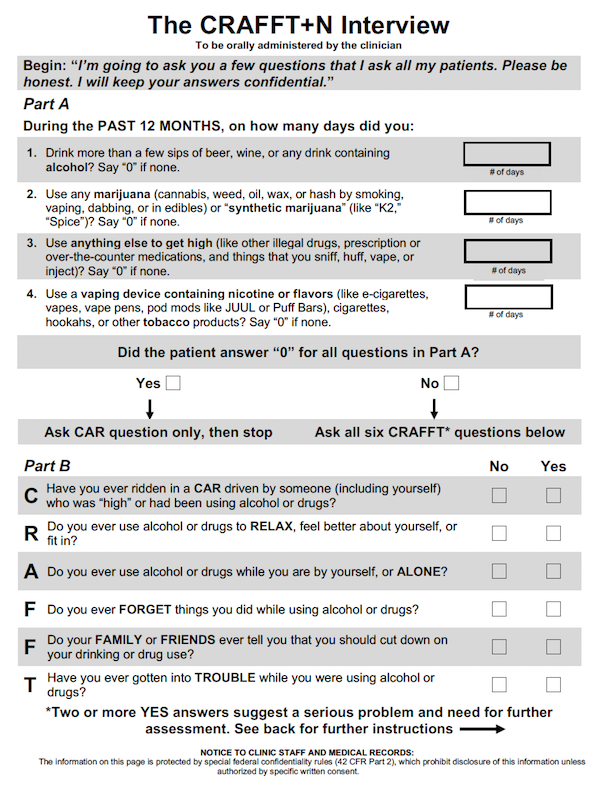

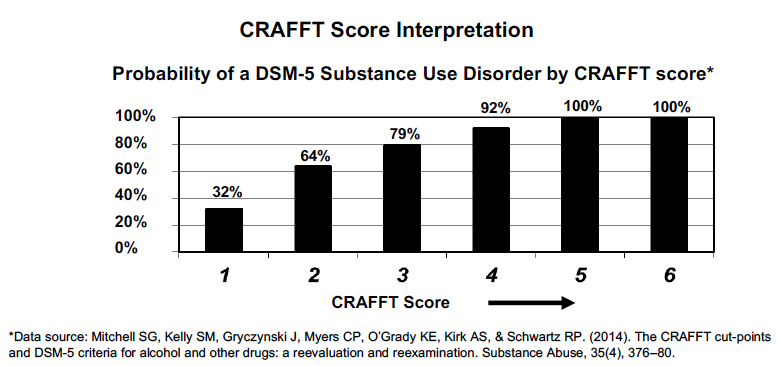

CRAFFT/CRAFFT-N Instrument

Score Interpretation

Additional Notes

Sensitivity and specificity: 76% and 92% / 80%-94%

Knight JR et al. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153(6):591-6

Knight JR et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156(6):607-14

DAST-10 Instrument

These Questions Refer to the Past 12 Months

Score Interpretation

Each “Yes” = 1 and each “No” = 0

Additional Notes

Sensitivity: 85%-91%, Specificity: 71%-73%

(Skinner, 1982)

SQAS/SQDS Instrument

Score Interpretation

| Screen | Excessive Use | Use Disorder |

|---|---|---|

| SQAS | 1-7 | 8+ |

| SQDS | 1-2 | 8+ |

Additional Notes

Sensitivity / specificity: SQAS 88% / 84%, SQDS 97% / 99%

(Saitz et al, 2014)

TAPS-1 and TAPS-2 Instrument

For example, "In the PAST 12 MONTHS, how often have you used any prescription medications just for the feeling, more than prescribed or that were not prescribed for you?"

Score Interpretation

| TAPS SCORE | Risk Category | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No Use in Past 3 Months | Reinforce Abstinence |

| 1 | Problem Use | Brief Intervention |

| 2+ | Higher Risk | Treatment or Referral to Treatment |

Additional Notes

Sensitivity / specificity: [80%-90%] / [77%-92%]

Common Questions about Screening

Review Question

In screening the 19 yo patient who is your colleague’s daughter for substance use, you select which of the following screening tools as it is validated for use in adolescence and screens for all substances:

Substance use screening involves 3 steps

Setting the stage:

Using evidence-based screen:

Providing feedback:

Let’s explore more

Setting the stage for screening:

Scripts can help...

Non-pregnant adult:

Normalize

“Substance use can affect health, so I ask all my patients yearly about their use of nicotine, alcohol and other drugs.”

Pregnant adult:

Address stigma

“My pregnant patients often have questions or concerns about using nicotine, alcohol or other substances during pregnancy or before realizing they were pregnant. How about you?”

Adolescent:

Confidentiality

Speaking with patient alone: “Use of nicotine, alcohol, marijuana and other drugs, if any, during adolescence can affect health and development. What you tell me about that is confidential unless it would endanger yourself or someone else. Do you have any questions about that?”

Use Evidence-Based Screens, such as:

|

Do you smoke or use other nicotine products? |

||

|

Age 12-17: How many times in the past 12 months did you drink any alcohol (> a few sips)? Adults: How many times in the past 12 months have you had more than [4(men), 3(women)] drinks in one day?

SQAS |

||

|

How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription medication for non-medical reasons (like to get high)?

SQDS |

Give targeted feedback that’s brief and relevant to the patient’s level of use

“You are making healthy decisions about substance use. Let me know if you have any questions about substance use and health or concerns about a loved one’s substance use.“

“I’m concerned about how your drinking/smoking/using may be affecting your blood pressure control. What are your thoughts about that?”

“For women, the healthy limit is no more than 3 drinks in one day and it sounds like sometimes you are drinking a bit more than that. What do you think about that?”

“Is it alright if we talk a little more about your opioid use?”

Review Question

You are training your staff in the practice's new SBIRT workflow. Your SBIRT champion implementation team has determined, given your patient population's overall discomfort with completing electronic and paper forms, that the medical assistants will administer the evidence-based screening instrument verbally as they are rooming the patients and enter the results into the EHR for the provider to review.

One of the medical assistants expresses concern that asking patients about their substance use may offend them.

Which of the statements below is an example of normalizing communication when setting the stage for screening?

This is one example of a screening protocol integrated into the clinical setting...

Brief Interventions to Address Substance Use in Primary Care

Learning Objectives

Completion time: About 10 minutes

Brief Interventions: Stages of Change

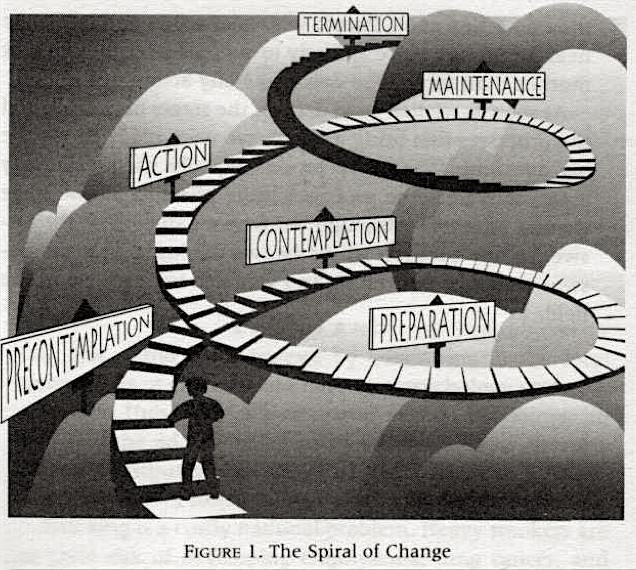

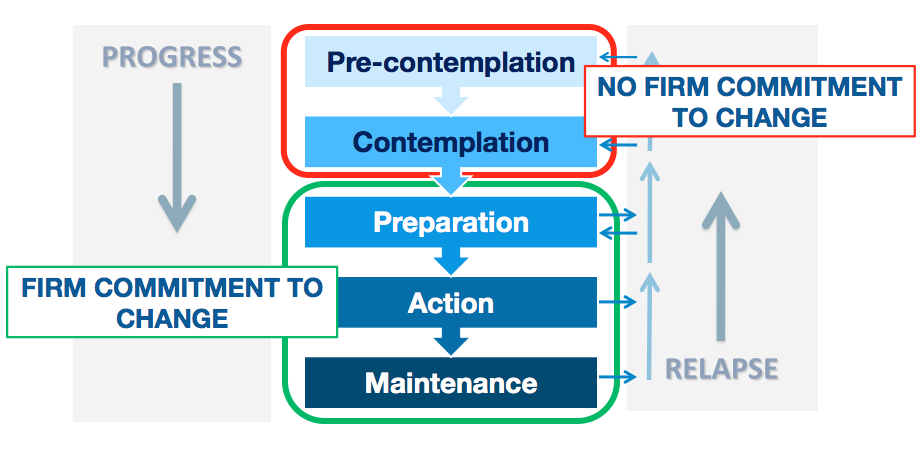

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM), first described in 1984 by Prochaska and DiClemente, recognizes change as a non-linear process involving several stages leading to successful behavior change.

| Stage | Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Pre-contemplation | No intention to change. Unaware of problem or possibility of successful change |

| Contemplation | Aware of the problem & considering a change, but no commitment to take action |

| Preparation | Intent to change and making small behavioral modifications toward change |

| Action | Taking decisive action to change |

| Maintenance | Working to prevent relapse and consolidate gains |

Brief Interventions: Facilitating change

The primary goal of the brief intervention is to positively facilitate the patient’s movement between the stages of change, helping them progress through the stages and avoid relapse.

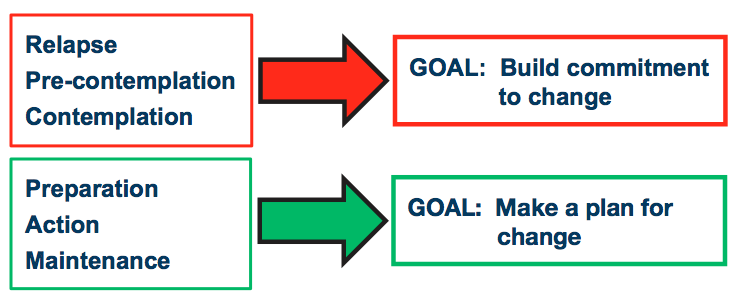

Brief Interventions: Goal by Stage

Brief interventions can be most effective when the goals of the intervention are tailored to the patient’s current stage of change.

Patients screening positive for substance use are likely to be in pre-contemplation or contemplation. They haven’t yet considered their substance use to be a problem or have been thinking about change but have not yet decided on following through with making the considered change.

Review Question

Your next patient is 43 yo and new to your practice coming in for back pain. They work as a landscaper and have been taking opioids as prescribed by their previous primary care physician for the last 10 years. Their previous physician recently retired.

On their substance use screen today, the patient screens positive for prescription opioid misuse, having resorted to buying hydrocodone pills off a co-worker whose mother recently passed from cancer, and taking more than previously prescribed doses.

You share the patient’s screening results with them while discussing their medical history and ask the patient their thoughts on their opioid use. The patient states “I don’t see there is any problem except my old doc retired, but now you’re my new doc and that should fix that problem.”

The patient’s current stage of change with regards to their opioid use is most likely:

Brief Interventions: Motivational Interviewing

“Motivational Interviewing is a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change.”

– Miller and Rollnick, 2012

In a Brief Intervention, the clinician applies MI Principles using OARS Skills with MI SPIRIT to elicit change talk while showing compassion and curiosity about a patient’s process of change.

Click on the 4 underlined terms above for more information

Expressing empathy conveys acceptance of the patient for who they are and what stage of change they are in. Acceptance facilitates change and recognizes ambivalence as a normal part of the change process. Reflective listening is a fundamental skill for expressing empathy.

A primary goal of this principle is to build rapport.

Change is motivated by a discrepancy between a patient’s perceived goals and values versus their current behavior. The clinician should elicit the patient’s own reasons for behavior change rather than provide the patient with external reasons for making a change.

A primary goal of this principle is to raise and/or heighten ambivalence.

By rolling with resistance, the clinician avoids argumentation and persuasion, which often leads to resistance to change. The patient shares their own perspectives on the change process, providing answers and solutions. Resistance is taken as signal by the clinician to respond differently.

A primary goal of this principle is to respect patient autonomy.

The patient’s belief in their capacity and capability to change is a key motivator. Behavior change is the patient’s responsibility. The clinician affirms the patient’s responsibility and internal resources for change.

A primary goal of this principle is to affirm the patient’s capability for change.

OARS is an acronym for the 4 key conversational skills used in MI

Open ended questions allow patients to express their own views and the physician to follow patients’ perspectives. An open-ended question cannot be answered with ‘yes’, ‘no’ or other single word response.

“What problems have you experienced as a result of your smoking?”

Actively listen for patient strengths, values, aspirations, positive qualities and reflect those to the patient in an affirming manner.

“You were able to meet your fitness goal despite the pandemic because of your perseverance and determination. Those strengths can help you cut back on your drinking.”

Reflective listening mirrors what a patient says in non-threatening manner, using the patient’s own word choices and phrasing when possible, to deepen the conversation. Reflective listening lets the patient know you are hearing them and seeking to understand their perspective. It is collaborative and nonjudgmental. Reflecting back change talk statements helps patients better connect with and understand their own motivations for change and resolve ambivalence.

(Patient: I’d stop using if I could afford treatment and didn’t have to miss work because of it.) “You’d stop using pain pills if there was an affordable, outpatient treatment option.”

Summaries are collections of change talk reflections that are used to highlight realizations, identify progress or themes, and manage transitions in the conversation. Ending a brief intervention with a strategic, collaborative summary reinforces the patient’s motivation for change.

“So we’ve talked today about your vaping and how while you find it relaxing and thought when you switched that it was less harmful than smoking, you’re worried now about it increasing your risk during the pandemic and its increasing cost.”

The Spirit of MI: PACE

Change Talk: fuel for change ‘DARN CATs”

Hearing one’s own reasons for change is a powerful motivator. Using open-ended questions is a great way to elicit change talk.

Listen for the following phrases to recognize change talk for reflecting back and summarizing to the patient.

Review Question

You are seeing a well-established, 68yo patient for follow up of their COPD after a recent hospitalization for COVID-19. He is thankful to have made it through a lengthy hospital stay and is embarrassed to disclose that he started smoking again soon after returning home but wants help to quit and stay quit:

“I don’t ever want to feel like I can’t breathe like that again. That was a really close call. I’ve got my third grandchild on the way and the rest of my retirement to enjoy.”

He doesn’t remember getting any medication or a nicotine replacement product while hospitalized but didn’t notice cravings or withdrawal then either, probably because “I was too sick to notice much of anything”. His cravings returned on the car ride home, when he noticed a half-smoked pack in the center console. Other than that, he doesn’t know why he resumed smoking as he feels ”tired and done with that” and gets more anxious than relaxed when he smokes now.

In the past he has tried various nicotine replacement products including patches, gum and lozenges. His longest time quit was 1 year, after the birth of his first grandchild, which motivated that quit attempt. He is smoking half a pack a day now, down from 1 pack a day.

Which of the following is a MI congruent statement you could make that would further support this patient’s efforts to quit smoking?

3 Steps of Brief Interventions

Decisional Balance to open discussion and explore ambivalence

Readiness Ruler to identify stage of change

Brief Discussion targeting stage of change to elicit change talk:

Let’s explore more.

3 Steps of Brief Interventions

Decisional Balance to open discussion and explore ambivalence

| START with | “So what do you like about [current behavior]___?” |

| THEN | “What do you dislike about [current behavior]___?” |

| END with |

Summary of pros and cons:

“You like that the opioids take away your pain, and you dislike that sometimes they make you too sleepy to function and it’s causing a lot of stress in your marriage.” |

3 Steps of Brief Interventions

Readiness Ruler to identify stage of change

“So where does that leave you: on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all ready and 10 is you’re ready to change today, how ready are you to [make behavior change]?”

| Score | Readiness | Stage of Change | Focus of Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-3 | Not Ready | Pre-Contemplation | Engage: raise awareness of problem |

| 4-7 | Ambivalent | Contemplation | Explore: heighten discrepancy |

| 8-10 | Ready | Preparation / Action | Plan for change / Sustain change |

3 Steps of Brief Interventions

Brief Discussion targeting stage of change to elicit change talk

Readiness Scores 0-3

What’s happened as a result of your drinking that you later regretted?

I forgot it was my turn to drive for carpool last week and that was embarrassing.

You were embarrassed by that. I am concerned that your drinking may be contributing to your anxiety rather than helping it.

Would you like more information about how alcohol may be impacting your health?

No, I don’t have time to talk about this now. It's really not a big deal anyways.

I respect that you aren’t ready to talk about your drinking more right now. Thanks for sharing what you have today. I will plan to ask you about it at our next appointment if that’s ok.

Readiness Scores 4-7

Why a [patient-stated number] and not a [lower number]?

I really shouldn’t forget to do things – I hate it when I do that. So maybe I should slow down some.

What would have to happen for you to go from a [patient-stated number] to a [higher number]?

I guess if it became a problem with work, I mean besides the carpool.

So you don’t like forgetting things and you’d definitely make a change if your drinking started interfering with work.

With that in mind, what do you think a change would look like when you are ready to cut back or stop?

I think I could work on not drinking during the week. Maybe stick to the weekends only.

That sounds like a good idea. How would you feel about me checking in with you about this the next time we see each other?

That sounds fine to me.

Readiness Scores 8-10

You’re ready to make this change. That’s a great decision for your health

I really am ready to cut back – I don’t want to live this way anymore. I’m tired of it.

Let’s identify the steps you can take to help you cut back. What do you see as a first step?

I guess I could start by drinking only once during the week and on weekends. Then I could work toward making sure I don’t drink more than one bottle of wine per week.

What people or groups in your life could help you while you work to cut back?

My book club would be helpful – they are all really supportive, and I know they would be there for me.

Offer follow up on plan progress in 4 to 6 weeks

Review Question

Your last patient of the day is a 38 yo ‘soccer mom’ here for her well woman exam. She screened positive for excessive alcohol use on the annual wellness form she completed online prior to her visit, which you review with her after confirming she has no current complaints for this visit and her benign health history is unchanged.

In discussing her drinking, using the decisional balance, she states that she likes drinking because it helps her relax and it’s just what her friends do when they get together. She dislikes that her drinking picked up during the pandemic and when she recently overheard her children, now teen and pre-teen, use the term ‘wine mom’ with their friends.

She says she is a 5 on the readiness ruler. Your next step is to ask:

This example video shows a brief intervention delivered in a primary care setting in under 3 minutes.

Note the three steps:

Medication Treatment for Nicotine Use Disorder in Primary Care

Learning Objectives

Completion time: About 5 minutes

Review Question

A 65-year-old male comes into your office for a check-up. He states that he has been feeling tired and short of breath but does not have any fevers or cough. He has a history of smoking 1 pack of cigarettes per day for the last 40 years.

He cannot climb a set of stairs and states that he has been hospitalized many times over the past year for pneumonia. He is prescribed inhaled corticosteroids along with ipratropium and albuterol.

Which of the following is most likely to decrease this patient's risk of hospitalizations for disease exacerbation and development of lung cancer?

As part of a patient’s preparation for quitting, encourage them to take the following steps (STAR):

Set a quit date, ideally within 2 to 4 weeks.

Tell your family, friends, and coworkers about quitting and ask for their support.

Anticipate challenges, particularly during the critical first few weeks. Challenges include nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

Remove nicotine products from your environment. Prior to quitting, avoid using the nicotine product in places where you spend a lot of time (e.g. work, home, car). Make your home nicotine-free.

CLICK HERE for behavioral therapy information

Combining Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy

First-line Medications for Nicotine Use Disorder

FDA-Approved Tobacco Cessation Medications

Discuss, prescribe, and document tobacco cessation medication(s).

| Medication | OTC/Rx | Use | Cost per dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine patch | OTC | Daily-Steady state | 2.00$-2.92$ (daily dose) |

| Nicotine gum | OTC | PRN-Craving rescue | 0.27$-0.82$ per piece (1.35-16.40$ for 5 to 20 pieces daily) |

| Nicotine lozenge | OTC | PRN-Craving rescue | 0.39$-0.40$ (1.95-8.00$ for 5 to 20 pieces daily) |

| Nicotine inhaler | Rx | PRN-Craving rescue | 2.77$ per cartridge (16.62-44.32$ for 6-16 cartridges daily) |

| Nicotine nasal spray | Rx | PRN-Craving rescue | 6.11$ per 40mg or 80 sprays average daily |

| Bupropion SR 150 | Rx | Daily-Steady state | 0.99-1.13$ (daily dose) |

| Varenicline | Rx | Daily-Steady state | 8.42$ (daily dose) |

Click on each medication for more information

n/a

Review Question

A 58-year-old woman presents to her family physician for an annual checkup. During the visit, the patient asks her physician for help quitting smoking cigarettes. She has unsuccessfully tried quitting several times previously and has also failed prior attempts with meditation and exercise. The physician prescribes a partial agonist of the nicotinic receptor to aid the patient in cessation.

Which of the following is a potential side effect of this medication?

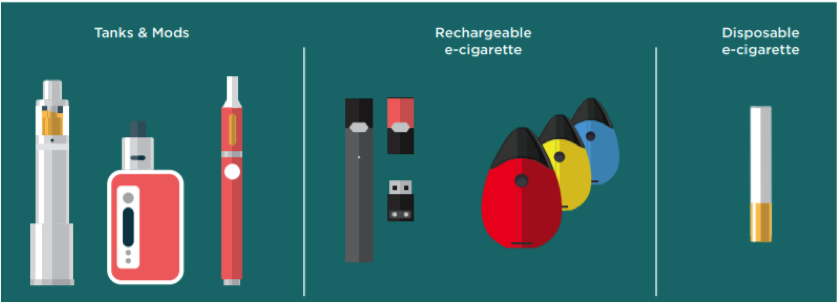

About Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS)

| What are ENDS? |

| Are ENDS less harmful than cigarettes and other forms of tobacco? |

| Can ENDS be used for tobacco cessation? |

| What medications can be used for patients wanting to quit ENDS? |

Click on each question for more information

What are ENDS?

Are ENDS less harmful than cigarettes and other forms of tobacco?

E-cigarette aerosol generally contains fewer toxic chemicals than the deadly mix of 7,000 chemicals in smoke from regular cigarettes. However, e-cigarette aerosol is not harmless. It can contain harmful and potentially harmful substances, including nicotine, heavy metals like lead, volatile organic compounds, and cancer-causing agents.

Can ENDS be used for tobacco cessation?

What medications can be used for patients wanting to quit ENDS?

Use of Combination Therapy

Some studies suggest that combining NRT with other medications may facilitate cessation. For example, a meta-analysis found that a combination of varenicline and NRT (especially, providing a nicotine patch prior to cessation) was more effective than varenicline alone.

Similarly, adding bupropion to NRT also improved cessation rates.

For smokers who could not cut down significantly by using the NRT patch, combining extended-release bupropion and varenicline was more effective than placebo, particularly for men and those who were severely nicotine dependent.

Nicotine use disorder, in the form of cigarette smoking, causes greater morbidity and mortality than any other single use disorder and all others’ combined risks.

Three in four adults with alcohol use disorder and 9 in 10 adults with other substance use disorders smoke tobacco.

Early-onset cigarette use is a significant predictor of lifetime drinking, more excessive alcohol consumption, and the subsequent development of lifetime alcohol use disorders.

Among individuals treated for alcohol use disorders, tobacco-related diseases were responsible for half of all deaths, greater than alcohol-related causes.

While concomitant tobacco smoking and other substance use are common, treating NUD may improve sobriety outcomes in the long term. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled tobacco cessation trials with smokers in treatment for substance use disorders found tobacco cessation interventions were associated with a 25% increased likelihood of sobriety from alcohol and other substances relative to usual care.

Review Question

A 35-year-old man presents to his primary care physician for a routine visit. He is in good health but has a 15 pack-year smoking history. He has tried to quit multiple times and expresses frustration in his inability to do so. He states that he has a 6-year-old son that was recently diagnosed with asthma and that he is ready to quit smoking.

What is the most effective method of smoking cessation?

Medication Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder in Primary Care

Learning Objectives

Completion time: About 5 minutes

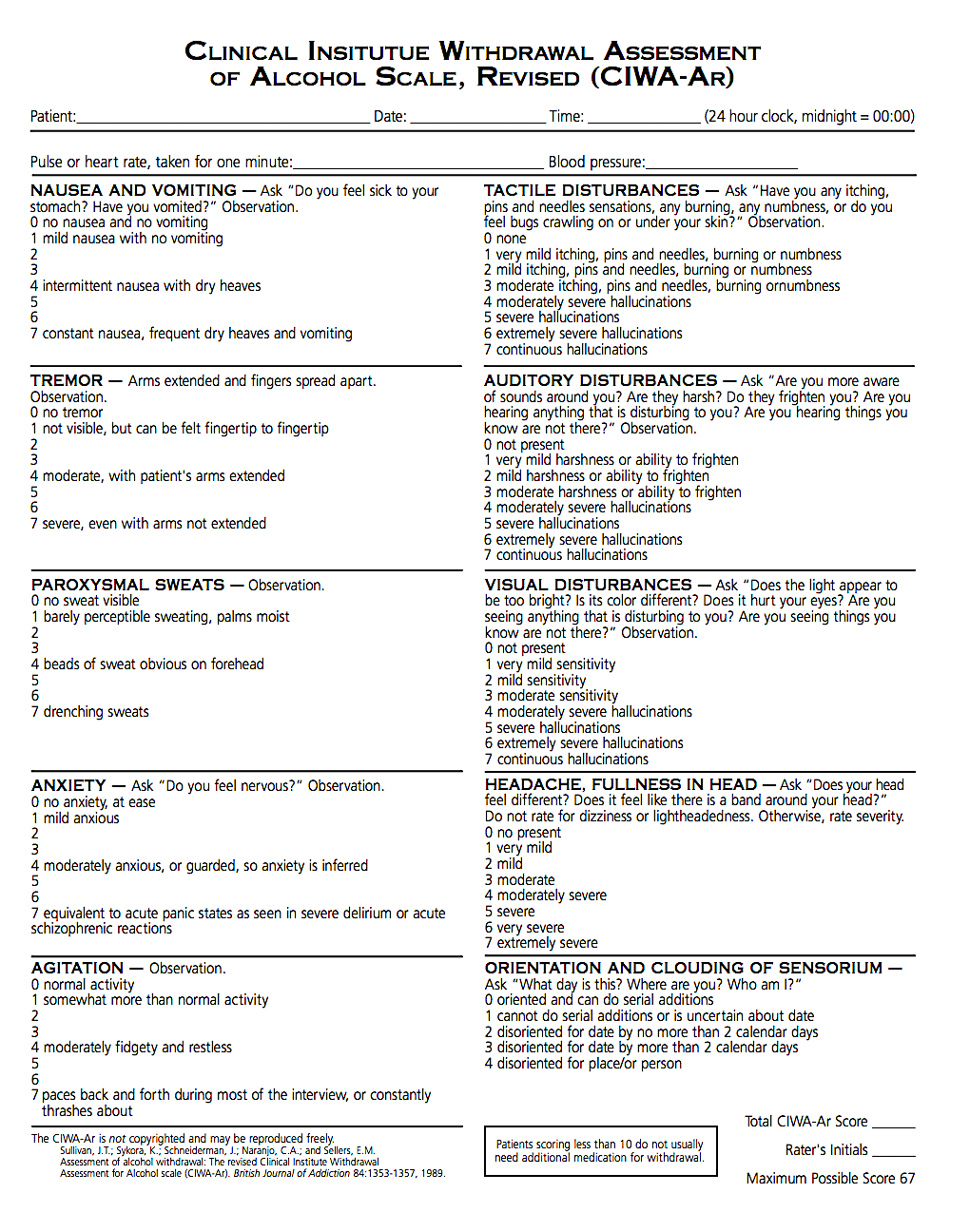

Medications for AUD Treatment in Adults - Withdrawal Management

| Medication | Route | Formulation | Recommended daily dose | Half-life | Cost | Side effects | Precautions | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal Management | ||||||||

Benzodiazepines | ||||||||

| Chlordiazepoxide (Librium) | Oral | 5mg, 10mg, 25mg | Symptom-driven or fixed dose-and-taper protocols | Intermediate acting (10-30 hours) | 0.18$-4.33$ per unit | Confusion, drowsiness, restlessness, irritability, tolerance, misuse | Dose adjustment in elderly, psychiatric patients, hyperactive aggressive pediatric patients | Historically preferred for patients with possible liver dysfunction |

| Diazepam (Valium) | Oral | 10mg | Symptom-driven or fixed dose-and-taper protocols | Long acting (20-100 hours) | 0.14$-4.88$ per unit | Confusion, drowsiness, restlessness, irritability, tolerance, misuse | Pregnancy, other substance use disorder, depression, seizures, glaucoma | ✱ |

| Lorazepam (Ativan) | Oral | 0.5mg, 1mg, 2mg | Symptom-driven or fixed dose-and-taper protocols | Short acting (10-20 hours) | 0.39$-0.56$ per unit | Confusion, drowsiness, restlessness, irritability, tolerance, misuse | Kidney disease, liver disease, glaucoma, psychosis, other substance use | ✱ |

| Phenobarbital (Luminal) | Oral | 15mg, 16.2mg, 30mg, 32.4mg, 60mg, 100mg tabs, 20mg/5ml elixir | Symptom-driven or fixed dose-and-taper protocols | 80-120 hours | 0.09$-0.79$ per unit | Somnolence, sedation, restlessness, could lead to respiratory depression | Other substance use, pregnancy, carcinogenic | Narrow therapeutic window, considered third-line to benzodiazepines and GABA-ergics; monitor blood levels or reflexes for toxicity |

GABA-ergics | ||||||||

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol) | Oral | 100mg, 200mg, 300mg | 800mg Day 1 tapering to 200mg Day 4 in divided doses | 35-40 hours | 0.20$-1.21$ per unit | Blurred vision, continuous back and forth eye movements, diarrhea, headaches | Use of MAO inhibitor, psychosis, history of suicide, light sensitivity | ✱ |

| Gabapentin (Neurontin) | Oral | 200mg, 300mg, 400mg | 600 - 1200 mg divided into 2 to 3 doses daily, tapering over 4 to 7 days | 5-7 hours | 0.14$-4.17$ per unit | Ataxia, dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue | Mental illness, seizures, pregnancy | Physical dependence and misuse have been noted |

| Valproic acid (Depakote) | Oral | ✱ | 500mg: One twice daily for 5 to 7 days | 4-16 hours | 0.32$-0.40$/ 250mg tab | Drowsiness, diarrhea, headache, weight changes | Breastfeeding, drowsiness | ✱ |

Medications for AUD Treatment in Adults - Relapse Prevention

| Medication | Route | Formulation | Recommended daily dose | Half-life | Cost | Side effects | Precautions | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse Prevention | ||||||||

On-label | ||||||||

| Acamprosate (Campral) | Oral | 333mg | 2 x 333mg tab po TID or 3 x 333mg tab po BID | 20-33 hours | $70-200 /month | Diarrhea, nausea, depression, anxiety | Dose adjustment for CrCl 30-50ml/min; unstable depression or suicidality | Patient selection: Impulsivity issues or protracted withdrawal symptoms |

| Disulfiram (Antibuse) | Oral | 125mg, 250mg, 500mg | 250 mg once daily | 60-120 hours | $54.90 /month | Metallic taste, dermatitis | Psychosis, DM, epilepsy, hepatic dysfunction, thyroid disease, renal impairment, dermatitis | Patient selection: highly motivated, monitored |

| Naltrexone (ReVia – oral) (Vivitrol – IM) | Oral, IM | 50mg tab, 380mg IM | 50mg tab po qday 380mg IM qmonth | 4-13 hours | Tabs: $130-300+ /month Single dose vial: $700-800 /month | Nausea, abdominal pain, constipation, dizziness, headache, anxiety, fatigue | Liver disease, renal impairment, history of suicide attempts | Patient selection: family history of alcohol dependency or concurrent Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) |

Off-label | ||||||||

| Gabapentin (Neurontin) | Oral | 200mg, 300mg, 400mg | 600-1200mg divided into 2 to 3 doses daily, tapering over 4 to 7 days | 5-7 hours | $8-250/ month | Ataxia, dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue | Mental illness, seizures, pregnancy | Physical dependence and misuse have been noted |

| Topiramate (Topamax) | Oral | 25mg, 50mg, 100mg tabs | 300mg/day po max | 19-23 hours | $9-500/ month | Numbness and tingling, change in taste, decreased appetite, concentration | Renal impairment with dose adjustment for CrCl < 70ml/min, depression, glaucoma | Patient selection: Can start non sober |

| Baclofen | Oral | 5mg, 10mg, 20mg tabs | no set upper limit, minimal impact below 60-80mg daily dose, 140-180mg typical in European literature, doses much higher reported | 2-6 hours | $60-300/ month | Drowsiness, dizziness, weakness, nausea, confusion, urinary retention | Renal impairment (cleared renally), h/o seizure disorder, avoid abrupt discontinuation, peptic ulcer disease, decreases GI motility, h/o psychosis | Typically reserved for patients non-responsive to or with contraindications to other medications, i.e., not used first-line, Non sober start okay, Titrate by 10mg q3 days to effective dose |

Alcohol Use Disorder treatment involves 2 phases

After abstinence initially achieved or started along with withdrawal management, relapse prevention can include:

Let’s take a closer look... click on each underlined term above

| Questions to Consider | Ambulatory Setting Safe | Inpatient or Residential Treatment Setting Safer |

|---|---|---|

| What is the patient’s home environment? | Patient has a safe, sober, supportive home environment | Patient lives alone, is undomiciled or has unstable housing, is experiencing active and ongoing trauma (abuse), or there is ongoing substance use by others |

| What is the patient’s cognitive status? | Patient is cognitively intact enough to safeguard their medication and take it as prescribed or have someone who is able and willing to help them manage the medications | Patients with cognitive impairment that precludes their adherence to medication protocols and who doesn’t have anyone who is able and willing to manage their medications for them |

| What is the patient’s current medical and psychiatric status? | Any underlying medical and/or psychiatric conditions are stable, and patient does not have a lowered seizure threshold | Underlying medical and/or psychiatric conditions are unstable, or lowered seizure threshold whether from medications (e.g., some neuroleptics, tramadol, theophylline), underlying seizure disorder, or concomitant cessation of other substances (e.g., benzodiazepines, GABA-ergics) |

| What is the patient’s prior experience with alcohol withdrawal? | Patient has no history of withdrawal seizures or delirium tremens | Patient with prior history of withdrawal seizures or delirium tremens is at heightened risk of these complications with subsequent withdrawal episodes, known as the ‘kindling effect’ |

| What is the patient’s current substance use pattern? | Patient is only using alcohol with or without concurrent nicotine use | Patient is using other substances, excepting nicotine, in addition to alcohol, especially substances with physical withdrawal syndromes requiring pharmacological management, i.e., benzodiazepines and/or opioids |

Click on each underlined term above for more information

Day 1: Take one every 6 hours

Day 2: Take one every 8 hours

Day 3: Take one every 12 hours

Day 4 and 5: Take one at bedtime

Do NOT drink ANY alcohol while taking this medication. Do not drive or operate heavy machinery while taking this medication. If withdrawal symptoms or cravings intolerable, notify clinician and/or seek emergency care immediately.

Oral adjuncts: folic acid 1mg daily, thiamine 100mg daily, ondansetron 8mg every 8 hours as needed for nausea/vomiting, trazadone 100mg or melatonin 6 mg as needed for sleep

Carbamazepine 200 mg:

Day 1: Take one every 6 hours

Day 2: Take one every 8 hours

Day 3: Take one every 12 hours

Day 4: Take one at bedtime

Valproic acid 500mg:

Take one twice daily for 5 to 7 days

If withdrawal symptoms or cravings intolerable, notify clinician and/or seek emergency care immediately.

Oral adjuncts: folic acid 1mg daily, thiamine 100mg daily, ondansetron 8mg every 8 hours as needed for nausea/vomiting, trazadone 100mg or melatonin 6 mg as needed for sleep

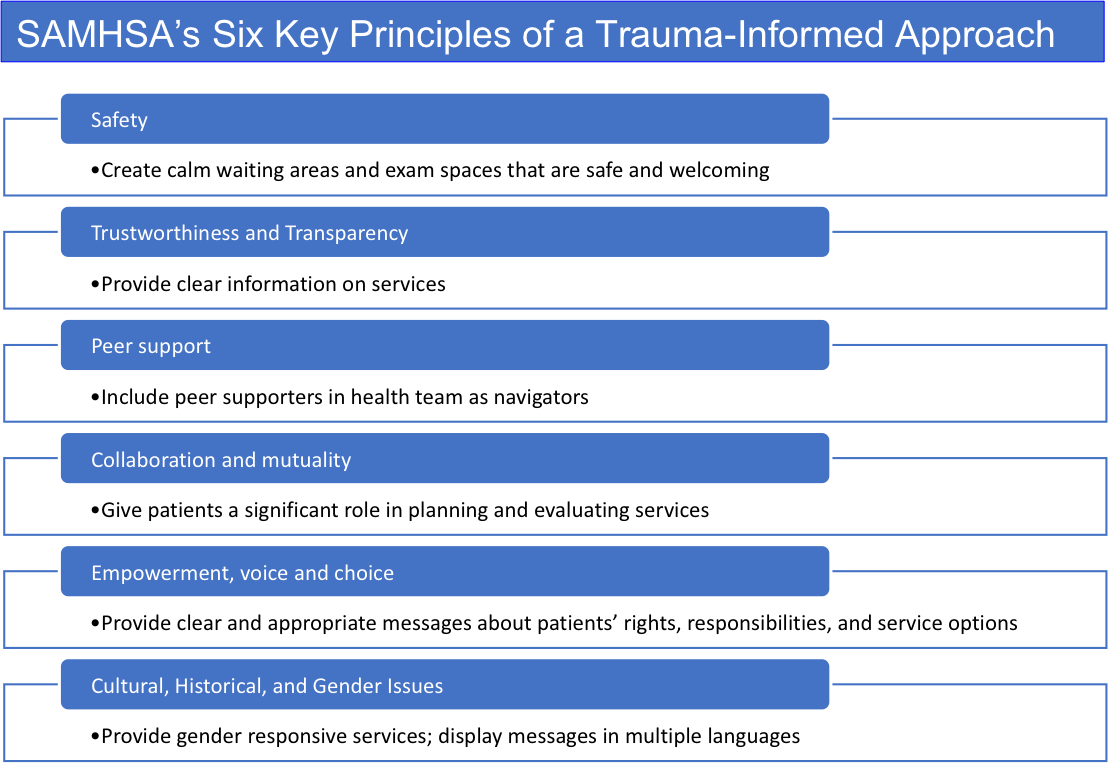

Many community-based treatment facilities incorporate a variety of behavioral therapies into their programming. Length of engagement with a program that uses evidence-based therapies is a better predictor of sustained recovery than type of therapy received. For patients with emotional, physical, sexual and/or verbal abuse histories, provision of or referral to trauma-informed services is crucial.

Behavioral therapies can be successfully delivered in the ambulatory primary care setting within integrated practices by a licensed counselor, within co-occurring behavioral health practices, and in formal SUD treatment programs in both outpatient and residential treatment settings. Most outpatient treatment programs offer sessions mornings, afternoons and evenings to accommodate caretaker, student and worker schedules, meeting for 2 hours 2 to 5 days a week, with weekend programming incorporating family programming.

Mutual-aid fellowships provide access to a sober support network with groups held around the world and around the clock. Each group will have their own ‘personality’. Encourage the patient to explore several groups for a few meetings each to see which one/s may be more helpful for them, if any. Fellowships help members celebrate recovery milestones. Attendees are not required to speak during meetings. Attending 90 meetings in 90 days has been shown to be helpful to achieving longer term fellowship participation and sobriety, as has having a sponsor, who is typically an established member of the fellowship with five or more years in recovery.

Review Question

Ms. B is a 20 year old patient here for a contraception visit. She screens positive on your practice’s alcohol screening questionnaire and on further discussion says she would like to quit, has tried cutting back herself but ‘that never works; if I have one, I’m not remembering the rest of the night’. She is a college student and was only drinking on the weekends, but now drinks 5 to 6 nights out of the week, ‘a lot, until I pass out, I guess 10-12 shots and a few beers too’. She denies use of any other substance except cannabis which she smokes once every week or two as it usually makes her more paranoid than relaxed. She takes a cannabidiol ‘gummy’ or two daily. She has no other medical problems or history, no psychiatric history, is not suicidal and is taking no other medications besides depo provera every 3 months. She is passing her classes this semester but barely. She has no history of seizures and no prior treatment for substance use of any kind. She moved back in with her parents, who are sober and supportive, after last semester as they hoped the move would help her cut back on ‘partying’. She wants to finish out the semester as if she takes a leave of absence she will lose a needed scholarship.

You suggest:

Prescribing Relapse Prevention Medication in Practice

Review Question

Mr. A is a 61 year old well known to your practice. He has diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia and was recently admitted to the hospital for shortness of breath and diagnosed with congestive heart failure. You are seeing him today for his post-discharge follow-up visit. In reviewing his hospital records prior to today’s visit, you note that he was also treated for alcohol withdrawal. In reviewing his inpatient test results, you note his echocardiogram was suggestive for alcoholic cardiomyopathy and his liver function tests were slightly elevated at less than two times the upper limit of normal.

During the visit with Mr. A, he somewhat sheepishly mentions that while he hasn’t started drinking again, he has been depressed since his recent divorce and thinking about ‘having a cold one, just one’ the last two days. He’s been stressed from this recent ‘health scare’ and with missing work. He is worried about how going back to drinking would affect his health.

You suggest:

Medical Complications of AUD: Providing care in long term recovery

Review Question

At a follow up visit 3 months later, Mr. A reports continued sobriety with no cravings. He has had no intervening episodes of sudden weight gain, chest pain or shortness of breath. Pre-visit lab results show his diabetes control is improving as are his cholesterol levels, especially triglycerides. However, his liver function tests are now two and a half times the upper limit of normal. His chief complaint today is ‘taking too many pills…I feel like a chicken pecking corn’. He asks about stopping the naltrexone.

You recommend:

Medication Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care

Learning Objectives

Completion time: About 5 minutes

Opioid Use Disorder Treatments

Use of medications to treat Opioid Use Disorders is recognized as the gold standard for treating OUD, as 4 out of 5 people with OUD will chronically relapse when treated with non-medication therapies alone. Medications have shown efficacy with and without behavioral counseling.

Many patients with OUD find the addition of behavioral therapies to be beneficial in addressing co-morbid mental health issues, including help in processing traumas such as current physical abuse or a history of childhood sexual abuse. Trauma is common in patients with OUD, especially women. Residential treatment services and sober living housing can be helpful for patients who don’t have a safe, sober, supportive home environment.

Most but not all behavioral treatment settings support patients taking Medications for Opioid Use Disorders (MOUD). Some programs do not permit patients receiving their services to continue or start MOUD. It is important to know which treatment providers you can refer patients to that will support the full spectrum of care for patients on MOUD.

Next we’ll explore the three classes of medications for treating OUD.

Review Question

Ms. C is a 32 yo new patient who comes to your office for renewal of her pain medication (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) which she has been taking for the last 4 years for back pain. She states her previous physician recently relocated out of the area. She started taking the opioid pills after a C-section. She has continued them as she found that they helped with back pain which began in her third trimester. Every time she has tried to taper off, her back pain returns along with pain in her other joints. Over the last 4 years she has gone from taking 1 to 2 a day to now taking 8 to 10 daily. She can barely get out of bed if she doesn’t have her medication but finds herself nodding out midday which scares her since she is home alone with her 4-year-old, who is quite active. She’d really like to get off the opioids especially since a cousin overdosed on pain pills last year, but she has resigned herself that her body is too sick without them.

What is the gold standard treatment for OUD which you can recommend to Ms. C?

FDA Approved Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in Adults

(Fully activates opioid receptors)

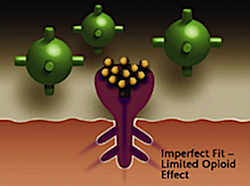

(Activates opioid receptor but produces a diminished response even with full receptor saturation)

(Competitively blocks opioid receptors, interfering with the rewarding and analgesic effects of opioids)

Click on each drug name for more information

| Drug name | Dosing | Image |

|---|---|---|

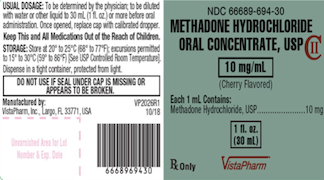

| Dolophine / Methadose | 60 to 120 mg/day |  |

| Drug name | Cost per dose |

|---|---|

| Dolophine / Methadose | $ 240 |

| Drug name | Dosing | Administration | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buprenorphine (Generic) | 8 to 16 (max 24) mg | Sublingual tablet |  |

| - Sublocade (Indivinor) | Initial: 300 mg monthly for 2 months; Maintenance: 100 mg monthly | Subcutaneous extended- release injection |

|

| Buprenorphine/Naloxone (Generic) | Formulation: 2/0.5 mg, 8/2mg Recommended Once-Daily / Maintenance Dose Target: 16 /4 mg Range: 4 /1 mg to 24 /6 mg | Sublingual tablet |  |

| - Suboxone (Reckitt Benkiser) | Formulation: 2/0.5 mg, 4/1 mg, 8/2mg, 12/3 mg Recommended Once-Daily / Maintenance Dose Target: 16 /4 mg Range: 4 /1 mg to 24 /6 mg | Sublingual film |  |

| - Zubzolv SL (Orexo) | Formulation: 1.4/0.36 mg, 5.7/1.4 mg, 8.6/2.1 mg, 11.4/2.9 mg Recommended Once-Daily / Maintenance Dose Target: 11.4 /2.9 mg Range: 2.9 0.71 mg to 17.2 /4.2 mg | Sublingual tablet |  |

| - Bunavail (Biodelivery Sciences) | Formulation: 2.1/0.3 mg, 4.2/0.7 mg, 6.3/1 mg Recommended Once-Daily / Maintenance Dose Target: 8.4 /1.4 mg Range: 2.1 /0.3 mg to 12.6 /2.1 mg | Buccal film |  |

| Drug name | Cost per dose |

|---|---|

| Buprenorphine (Generic) | $30-$180 (dose dependent) |

| - Sublocade (Indivinor) | $ 1,741.50 |

| Buprenorphine/Naloxone (Generic) | $90-$270 (dose dependent) |

| - Suboxone (Reckitt Benkiser) | $240-$900 (dose dependent) |

| - Zubzolv SL (Orexo) | $180-$540 (dose dependent) |

| - Bunavail (Biodelivery Sciences) | $ 550.52 |

| Drug name | Dosing | Administration | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naltrexone ER - Vivitrol (Alkermes) | 380mg monthly | Intramuscular injection |  |

| Drug name | Cost per dose |

|---|---|

| Naltrexone ER - Vivitrol (Alkermes) | $ 1,458.09 |

What are the advantages and disadvantages to providing MOUD within a primary care office-based setting (OBOT)?

| Advantages |

|---|

| Perceived as less stigmatizing than attending a traditional non-medication-based treatment program or an opioid agonist treatment program (methadone clinic) |

| Recognizes and reinforces that OUD is a chronic disease within the scope of regular medical practice – and that stabilizing a person’s OUD is important to their overall health |

| In many areas, specialty OUD treatment is not available or there are long waits for treatment services |

| Primary care clinicians who treat patients for chronic pain have an effective modality for addressing OUD that can inadvertently result from chronic pain treatment with opioids while still offering some analgesia |

| Disadvantages |

|---|

| May not provide enough structure and support for patients with complex or uncontrolled psychiatric morbidities |

| Doesn’t provide patients with a sober, safe, supportive recovery environment if their current home environment is lacking |

| Partial agonist therapy (e.g., buprenorphine) may not provide sufficient opioid receptor activation to stem cravings and withdrawal in a person with extremely high opioid tolerance (eg to fentanyl) |

| Patients wanting non-agonist medication treatment option (eg naltrexone) will need opioid withdrawal management and to tolerate a 7 to 10 day ‘wash-out’ period before beginning treatment, that is often not well tolerated nor successfully completed outside of a controlled setting |

Deciding if a patient is a good candidate for OBOT

Click on each question for more information

Review Question

In discussing OUD treatment options with Ms. C, she shares that her priority is to find a treatment she can fit into her busy days caring for her pre-schooler.

What treatment would be most likely to meet her priority?

Initiating OUD Medication Treatment

Let’s explore how to start patients on each of the three MOUD options:

Click on each medication for more information

Initiating Buprenorphine

Patients can be started on buprenorphine MOUD in office or at home, 8 to 24 hours after their last opioid use. Initial starting dose of 2 to 8mg on Day 1 is titrated over several weeks with at least weekly visits to reach a stable, steady-state dose that markedly decreases or eliminates cravings and opioid use. Therapeutic doses range from 6 to 24 mg daily.

Urine drug screening, Texas prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) database review, treatment consent and contract review and signing are standard components of the first visit.

At home induction can be easier to incorporate into a primary care workflow than in office induction. Many patients, familiar with buprenorphine either from prior personal experience or hearing the experiences of friends, family or acquaintances, will be able to explain buprenorphine induction strategies to successfully avoid precipitated withdrawal. Other patients will need their prescribing clinician to explain the risk of precipitated withdrawal if buprenorphine is started too soon after the patient’s last opioid, how long a wait is typically needed after last opioid use for the given opioid or opioids the patient is using to start buprenorphine, the signs and symptoms of withdrawal to look for the patient to know they are in sufficient opioid withdrawal to take their first dose of buprenorphine, and how to titrate dose the first day to week of treatment.

Click here for clinician Quick Start Guide which includes sample protocols and forms as well as links to additional resources.

Since January 2023, the X-waiver requirements have been eliminated for prescribing buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder. Any clinician with Schedule III controlled substance prescribing authority (i.e. a standard DEA certificate) can treat patients with buprenorphine using their regular DEA number and with no limits to the number of patients they may treat.

Initiating Methadone

Initiating Naltrexone

Continuing OUD Medication Treatment

Discontinuing OUD Medication Treatment

Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) for All Patients with OUD

Click on the underlined text above for more information

Key points to emphasize when counseling patients on opioid overdose prevention include:

Naloxone. . .

. . . is an opioid antagonist with zero abuse liability

. . . has no effect on a person who does not have opioids in their system or who is not physically dependent on opioids

. . . has a half-life of 30-90 minutes which is shorter than that of any known opioid. Once naloxone wears off, overdose can recur making it essential to get the person emergent medical care

. . . comes in a variety of easy to administer formulations

. . . may need to be re-dosed in 3 to 5 minutes after the first dose if a person has overdosed on a potent opioid such as fentanyl

Review Question

Ms. C would like to try buprenorphine for treating her OUD. In addition to a referral to a nearby colleague who is waivered to provide OBOT, you provide Ms. C with:

Providing Trauma-Informed, Stigma-Free Care

Learning Objectives

Completion time: About 5 minutes

Question

Mr. T is a 62 yo with DM, HTN, s/p MI 3 weeks ago, presenting for post hospitalization follow up and re-engagement in care. His last visit to the practice was 3 years ago. A brief review of the EHR shows the patient engages with the practice regularly for 6 months to a year, then is ‘lost to follow-up’ for one to 3 years, re-engaging care after hospitalizations (twice for DKA, once for hypertensive crisis, prior to his recent MI). He has a remote history of cocaine use disorder in his mid-20’s to 30’s after an honorable military discharge following several tours of duty. He runs his own home repair business with his adult children.

What in his history suggests possible trauma?

What is Trauma?

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

In the mid-1990s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente conducted a study to understand the relationship between childhood traumatic events and adult health. The survey asked questions about exposures to child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, drug and alcohol misuse among household members, and other traumatic stressors. (Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg et al, 1998)

In the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (or ACEs), almost two thirds reported at least one ACE while more than 1 in 5 reported THREE or more ACEs.

Later studies have found that ACEs disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities. For example, 61% of Black non-Hispanic children and 51% of Hispanic children have experienced at least one ACE compared to 40% of White non-Hispanic children.

As the number of ACEs increase, the risk for health problems later in life also increase, including alcohol use disorder, obesity, COPD, depression, liver disease, cancer, stroke, and sexually transmitted infections (to name a few), amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars each year in economic and social costs.

What is the Relationship of ACEs to Substance Use and Related Behavioral Health Problems?

Early initiation of drinking and illicit drug use

Lifetime depressive episodes, sleep disturbances, high-risk sexual behaviors all show a graded, dose response effect with ACEs

SAMHSA, Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies, June 2018

Click on items in blue text for more information

Review Question

Ms. A is a 31 yo with anxiety and insomnia presenting with recurrent UTI signs and symptoms. This is her 3rd urgent/walk in visit in the last 4 months for the same complaints, which were previously treated empirically with SMP/TMX then ciprofloxacin. On reviewing her history in the EHR, you notice Ms. A’s last counseling note from the therapist recently integrated into the practice’s care team, mentions a history of childhood sexual abuse and current emotionally abusive partner, as well as ongoing cannabis use since the patient’s mid teens. Also noted is a strong and supportive relationship with her older sister. She is also overdue a well woman exam. As you are taking the patient’s HPI with her today for this urgent care visit, she denies fever, chills, nausea and vomiting, but declines to answer questions about recent sexual activity, stating that she knows to void after intercourse and that she has no abnormal vaginal discharge. During the physical exam she agrees to palpation of her abdomen including suprapubic area, which is tender, and back which reveals no CVAT. She adamantly refuses a GYN exam now or scheduling a future well woman visit. She is reluctant to provide a urine specimen as she is worried you will send it for a urine drug screen as well, the results of which could jeopardize her job.

Which of the following is NOT consistent with providing trauma-informed care to Ms. A?

Trauma-Informed Care: Avoiding Re-Traumatization

An essential goal of trauma-informed care is to avoid re-traumatization. Respecting patient autonomy and supporting patient empowerment are key. You and other members of the patient’s care team can:

Respect patient autonomy through

Support patient empowerment through

Providing Trauma-Informed Care

A simple, yet powerful way to look at trauma-informed care is to consider shifting the paradigm from “what is wrong with you?” to “what happened to you?”

To provide effective care we need to understand the life situations that may be contributing to the patient’s current problems.

Many current problems faced by the persons we serve may be related to traumatic life experiences.

People who have experienced traumatic life events are often very sensitive to situations that remind them of the people, places or things involved in their traumatic events.

These reminders, also known as triggers, may cause a person to relive the trauma and view the healthcare setting/organization as a source of distress rather than a place of healing and wellness.

Trauma-informed care is most effective when implemented practice-wide, not patient or provider specific.

Trauma-informed Clinical Practices:

Review Question

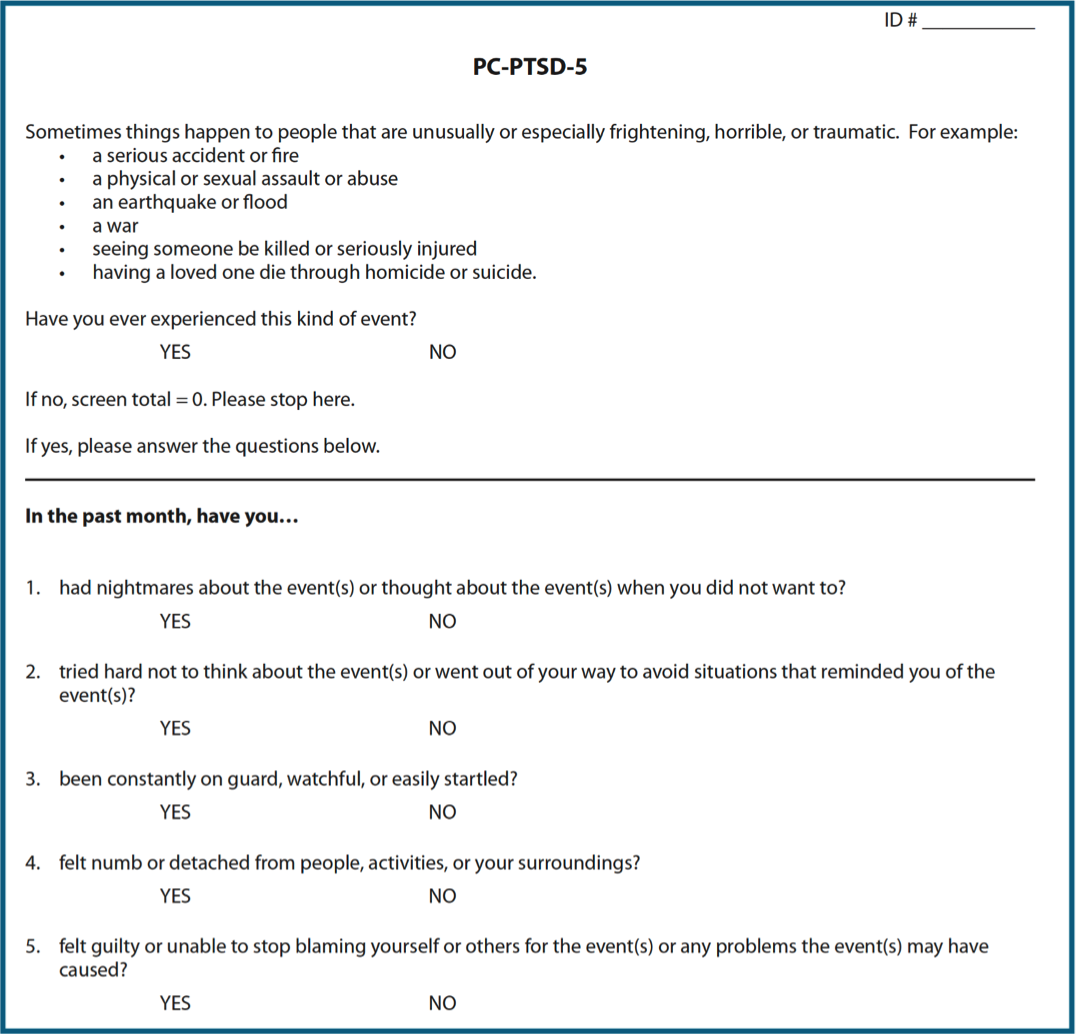

Mrs. C is a seventy-six-year-old longstanding patient of yours with well controlled hypertension presenting for routine follow up and a flu vaccine. Recently the practice has implemented a PTSD screen as part of the intake process, and the medical assistant has flagged this patient’s screen as positive in the electronic health record. In discussing the positive screen with Mrs. C, you are surprised to hear about a traumatic event now almost two decades past, that has had a long- lasting impact on her sleep and independence, which she has not felt was something to bring up at a medical visit. The incident happened at a gas station one evening as she was traveling between Houston and McAllen which she often did for work before retirement. She was assaulted and robbed at gunpoint and since then has had sleep issues and has her spouse do the refueling of all their vehicles as she panics pulling into gas stations. As her spouse is a few years older than her with several chronic health conditions, Mrs. C is worried about what will happen if he passes first in terms of her independence and mobility. She is grateful, as are you, for the opportunity to address her concerns this visit.

Which of the following statements does NOT represent an empathetic, validating response to Mrs. C’s trauma disclosure?

For Integrated Practices: Seeking Safety

Developed in 2002, Seeking Safety is an evidence-based, counseling intervention that addresses co-occurring substance use disorders and PTSD. It was first developed for women then expanded to men and can be delivered individually or in a group setting:

Sessions focus on:

Empowerment is key

Najavits, L.M., (2002) Seeking Safety A Treatment Manual for PTSD and Substance Abuse. New York: Guilford Press

Review Question

Mr. P is a 44-year-old new patient presenting with chronic back pain from an injury 2 years ago. As you enter the room and greet the patient you sense they’re on edge and ask if everything is ok so far this visit. The patient tersely relates overhearing front desk staff saying he is ‘drug seeking’ when letting the medical assistant know Mr. P has completed the check in process and is ready to be roomed. He also felt judged by the medical assistant after he answered yes to smoking cigarettes and drinking alcohol on the standard substance use screen the practice uses, noticing her tone changing from welcoming and conversational to cold and curt for the rest of the rooming process. You acknowledge the patient’s concerns, and he tells you he was thinking of just walking out without being seen, but really wanted to meet you as you are taking care of one of his friends who also has chronic pain. You’ve significantly helped the friend get a better handle on the pain without resorting to opioids. Mr. P has sought care from several other providers, who offered opioids when short trials of non-narcotic pain relievers didn’t help, but he is adamantly against taking opioids since his twin died of an opioid overdose 4 years ago, when the patient found him unresponsive during a camping trip, having not realized his brother had relapsed.

What experiences did this patient have this visit that were stigmatizing and what were trauma-informed?

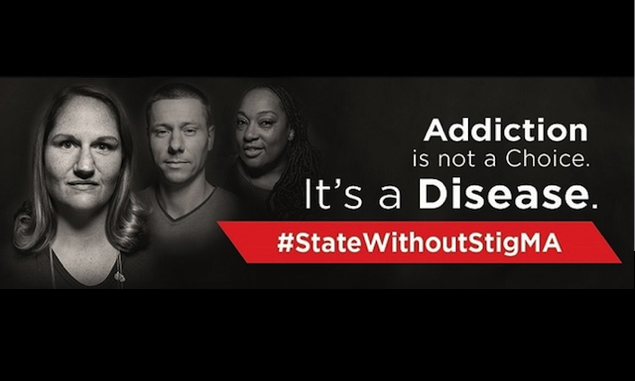

Stigma: A Barrier to Care

Stigma and Medications for Substance Use Disorders (MSUD)

Common myths:

The Role of the Primary Care Practice & Provider in Addressing Stigma

One of the most affirming and easiest changes that can be made is to change the language we use when talking about substance use disorders.

Other ways to decrease stigma:

Post-Training Survey and CME/CEU Certificate

Instructions: Complete all the modules then take the post-training survey to claim CME/CEU

Please watch the entire video and then take the post-training survey to claim CME/CEU

When completing the Post-Training Survey, use the same identifier details provided during registration and the Pre-Training Survey: